Eric Birkhauser’s “open air” ZIPcycle velomobile concept was featured in a Bicycle Design post last year. He points out that the feedback received from readers in the comments (and from an earlier post) directly led to his redesign… the ZIPcycle 2.0. In order to prove the concept, Eric’s next step is to build a working prototype, and he has launched an Indiegogo campaign to raise funds needed to accomplish that goal.

Eric Birkhauser’s “open air” ZIPcycle velomobile concept was featured in a Bicycle Design post last year. He points out that the feedback received from readers in the comments (and from an earlier post) directly led to his redesign… the ZIPcycle 2.0. In order to prove the concept, Eric’s next step is to build a working prototype, and he has launched an Indiegogo campaign to raise funds needed to accomplish that goal.

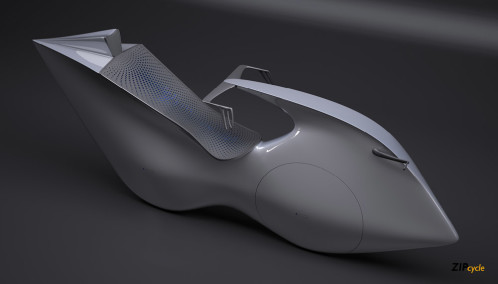

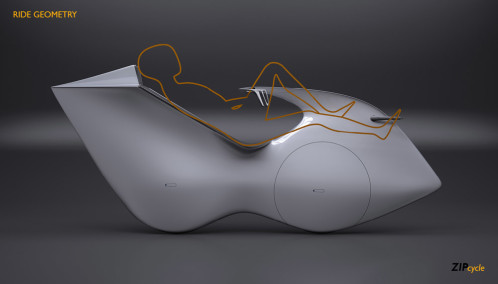

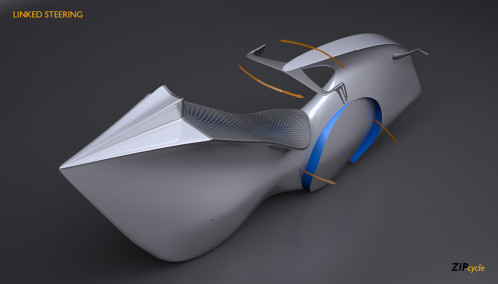

The basic idea behind the ZIPcycle is to increase efficiency so that the vehicle requires less input for more output. To accomplish that, Eric’s design is (not surprisingly) “a recumbent bicycle that has been aerodynamically optimized for less exertion and higher cruising speeds.” As he further explains:

The basic idea behind the ZIPcycle is to increase efficiency so that the vehicle requires less input for more output. To accomplish that, Eric’s design is (not surprisingly) “a recumbent bicycle that has been aerodynamically optimized for less exertion and higher cruising speeds.” As he further explains:

“The standard upright bicycle hits an aerodynamic wall as it approaches 20 mph. If you have ever had the experience of riding with a 20 mph tailwind, you have experienced the elimination of this wall. By shifting and streamlining the body position of the rider, and enclosing the drag causing elements of the bicycle in a fairing, this wall again can be eliminated. The modern road bicycle and rider has roughly a drag coefficient of .80, the ZIPcycle effectively drops the coefficient to .14. This reduction in drag means that about 40% less energy is required to maintain a cruising speed of 20 mph. While the average commuting bicycle cruising speed is 12 mph, imagine easily doubling that cruising speed, while eliminating the handlebar strain and seat pressure of the conventional bicycle, and preserving the open air experiential component of the conventional bicycle. “

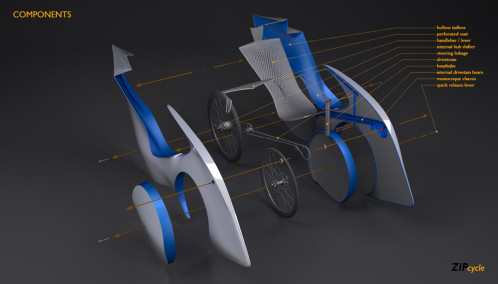

Key Components of the ZIPcycle Design

Key Components of the ZIPcycle Design

- A die stamped monocoque aluminum chassis

- Linked steering mechanism, connecting the handlebar to the steering tube and front wheel fork (a mechanism found in underseat steering recumbent bicycles)

- Hub shifting in the rear wheel to accommodate the necessary gearing range

- Lubricated bearings, gears, and chains enclosed within the chassis in an internal driveshaft beam (so you will never again get grease on your clothes)

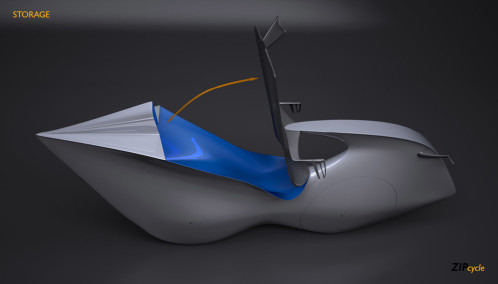

- Hollow tail-box, accessible by tilting the ventilated seat forward, spacious enough for a medium sized bag

- Option for an in-hub motor and lithium ion battery pack to provide hill and acceleration assist functions for cyclists in hilly and mountainous regions

- Additionally, while the intent of this concept is to preserve the traditional open-air experience of the bicycle, the chassis has been designed in tandem with a fairing, and a fairing will be a future optional component of the design.

You can see a few renderings of the ZIPcycle 2.0 in this post, but I encourage you to visit Eric’s project page for more.

Leave a Reply to Androo Cancel reply